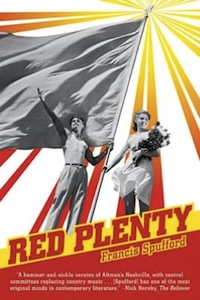

What a wonderful world we live in where a book like Francis Spufford’s Red Plenty can be published! It came out in the UK in 2010 and it has just been published in a new US edition.

It’s not SF. It’s not really fiction, though it’s not non-fiction either. It’s something strangely between the two, a fictionalised non-fiction book about the Soviet Dream. Reading it partakes of some of the pleasures of reading especially geeky SF, and some of the pleasure of reading solid well-written nonfiction on a fascinating subject. It’s about history, economics, how technology and ideology interact, and how theory and practice are different, with examples. What it’s most like is reading an extended version of one of Neal Stephenson’s more adorable infodumps, only with footnotes and a proper end. Or it’s as if a non-fiction writer got carried away when giving examples and started to make them into actual stories with characters. Indeed, that may be what happened and it’s very relevant to the book—the USSR were starting off with textbook examples that were going to rationally want x of this and y of that, except that they didn’t have those examples, they had people. And when Khrushchev said it, he really thought that they would bury us.

“But why are you interested in the economics of the USSR, Jo?” I hear you ask.

I’m not. Or rather, I am vaguely, because I’m vaguely interested in pretty much everything (except pirates and zombies) but the economics of the USSR might never have got to the top of the long list of pretty much everything if this hadn’t been written by Francis Spufford. Spufford is the author of the wonderful memoir The Child That Books Built and the even more wonderful The Backroom Boys (post). I liked The Backroom Boys so much that if he’d decided to write a book about the history of barbed wire next I’d have thought hmm, barbed wire, well, I guess that must be something really interesting then. Who knew? He has that addictive readability factor.

I find it seems more constructive to think of the book as non-fiction, because it’s a thesis that is being examined. That thesis is that a whole lot of people, some of them very intelligent, believed that they could make a command economy work. They were wrong. The book delved into why were they wrong, what went wrong, and the question of whether it could be otherwise. The book isn’t interested in the kind of things you usually get in history books, it’s much more focused on the geeky fields of technology and economics and and logistics. Spufford examines all this from several angles, from the thirties to 1968, and with characters, some of whom are historical people and some of whom aren’t.

You may be thinking that this is really odd. You’re right. It’s really odd. It’s not like anything else. It’s also amazing, because he makes it work. At first I thought I’d prefer a plain old non-fiction book about this stuff, and then I started to see what he was doing and really got into it. The characters, the points of view, really immerse you in the worldview of people who believe what they believe, as in fiction. And the thesis, the argument, is the thing that would be a story if the book were a novel. He’s using the techniques of fiction in the service of non fiction, and he makes it work.

This is from near the beginning:

If he could solve the problems people brought to the institute, it made the world a fraction better. The world was lifting itself up out of darkness and beginning to shine, and mathematics was how he could help. It was his contribution. It was what he could give, according to his abilities. He was lucky enough to live in the only country on the planet where human beings had seized the power to shape events according to reason, instead of letting things happen as they happened to happen, or letting the old forces of superstition and greed to push people around. Here, and nowhere else, reason was in charge.

You can’t do that kind of thing without a person to do it through, and Spufford keeps on doing it with different people, over time, so that we can see how it all works, or rather, ought to work in theory but doesn’t in practice.

My favourite part of the book was the bit about the viscose factory. (Viscose factories, huh? Who knew?) There are several chapters from different points of view all about the problems of the viscose factory, and what it amounts to is an examination and a critique of the idea of measuring the wrong things and valuing the wrong things. It would make a wonderful movie. It starts with a bureaucratic report about a machine destroyed in an unlikely accident, and a new machine being ordered. Then we move to these factory workers who carefully set everything up and destroyed the machine because they can’t possibly make their target unless they have a new machine, and this is the only way they can get one. Altering the target isn’t a possibility. Buying a new machine isn’t a possibility. This crazy scheme is the only thing. But then we see Chekuskin, the “fixer” who makes everything work by getting favours from everyone because everyone wants favours back. He’s trying to fix the problem that what they’ve been assigned is the same old machine that couldn’t meet the target in the first place. He meets a contact from the machine factory in a bar, he loosens him up with drinks and asks what the real problem is:

Although your clients want the upgrade, and believe me we would like to give them the upgrade because it is in fact easier to manufacture, we cannot give them the upgrade because there’s a little itty-bitty price difference between the upgrade and the original.

Price difference. Chekuskin could not think of an occasion in thirty years where this had been an issue. He struggled to apply his mind through the analgesic fug.

“All right, the upgrade costs more. Where’s the problem? It’s not as if my guys are going to pay for it themselves. It all comes out of the sovnarkhoz capital account anyway.”

“Ah ah ah. But it doesn’t cost more. That’s the delightful essence of the problem, that’s what you’re not going to be able to solve. It costs less. It costs 112,000 rubles less. Every one that leaves the factory would rip a great fucking hole in the sales target.”

… “I still don’t get it,” said Chekuskin. “Why should the upgrade cost less?”

“We didn’t get it either,” said Ryszard. “We asked for clarification. We said ‘Why is our lovely new machine worth less than our old one?’ And do you know what they said, the sovnarkhov? No? They pointed out that the new one weighs less.”

When it works at all, it works because people cheat the system.

Spufford writes beautiful sentences and memorable images that stay with you, and in this book he’s writing about an ideology that’s more alien than a lot of science fiction.

This is another one of those books, like Debt (post), that SF readers will enjoy for a lot of the same reasons we enjoy SF.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two poetry collections and nine novels, most recently the Nebula winning and Hugo nominated Among Others. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.